A Heritage-Based Approach to Adaptive Reuse

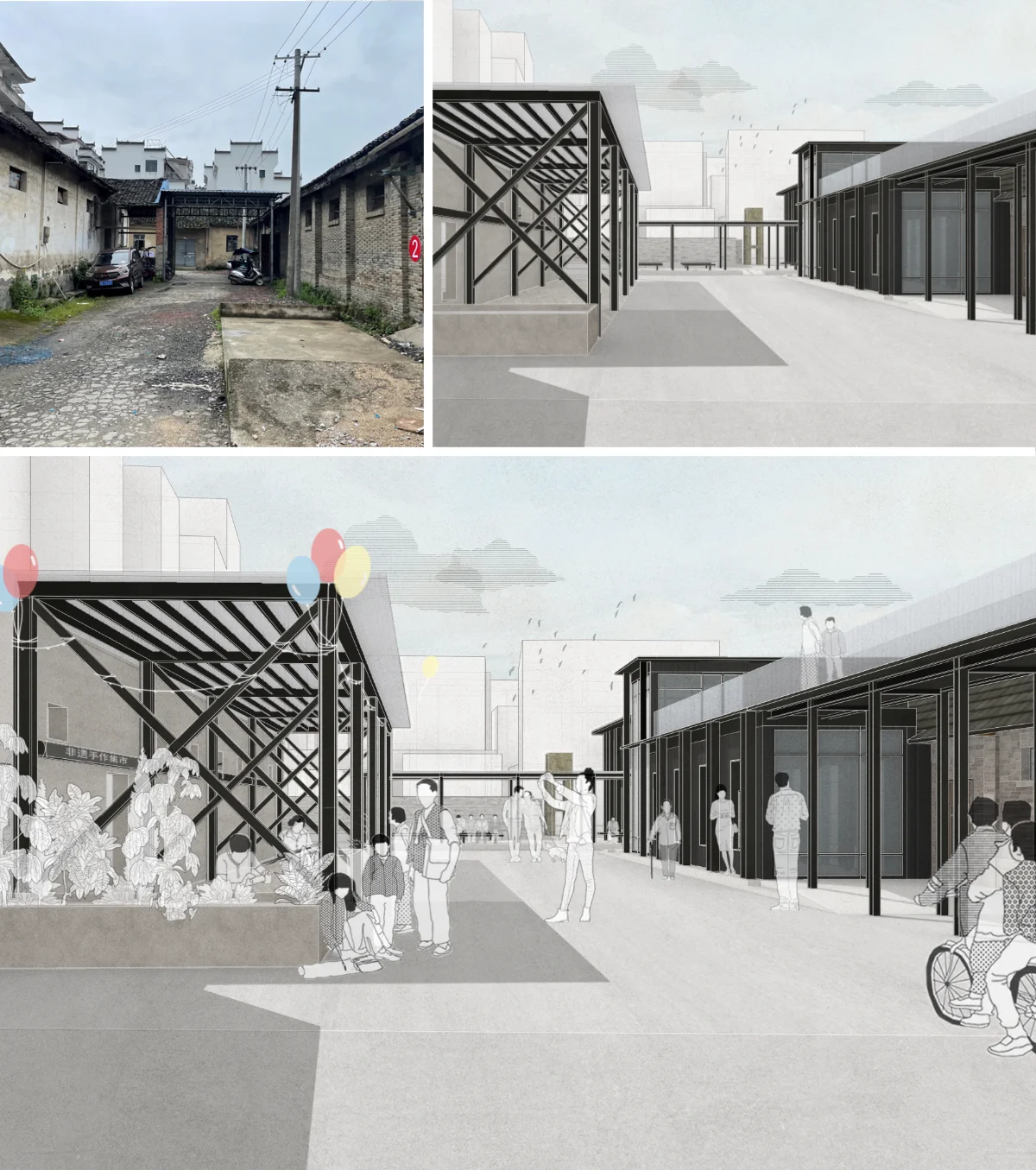

Reimagining the Old Grain Station in Qinghua Town

Situated in Qinghua Town, Wuyuan County, Jiangxi Province, the site was selected in collaboration with local authorities. Known for its scenic villages, field research revealed many neglected and underused spaces with overlooked potential within the region. Following an initial value assessment, the Old Grain Station was selected for its structural integrity, layered history, and strategic location, offering a distinct opportunity to transform it into a cultural space for both students and visitors.

Heritage has become increasingly present in our contemporary environment—an often deliberate mix of old and new that we have grown accustomed to. Yet the widespread popularity of adaptive reuse—especially involving industrial structures—has also contributed to the commodification of heritage, prompting the question:

How can "ordinary" industrial sites, such as the Old Grain Station in Qinghua Town, be reimagined through a heritage-based approach?

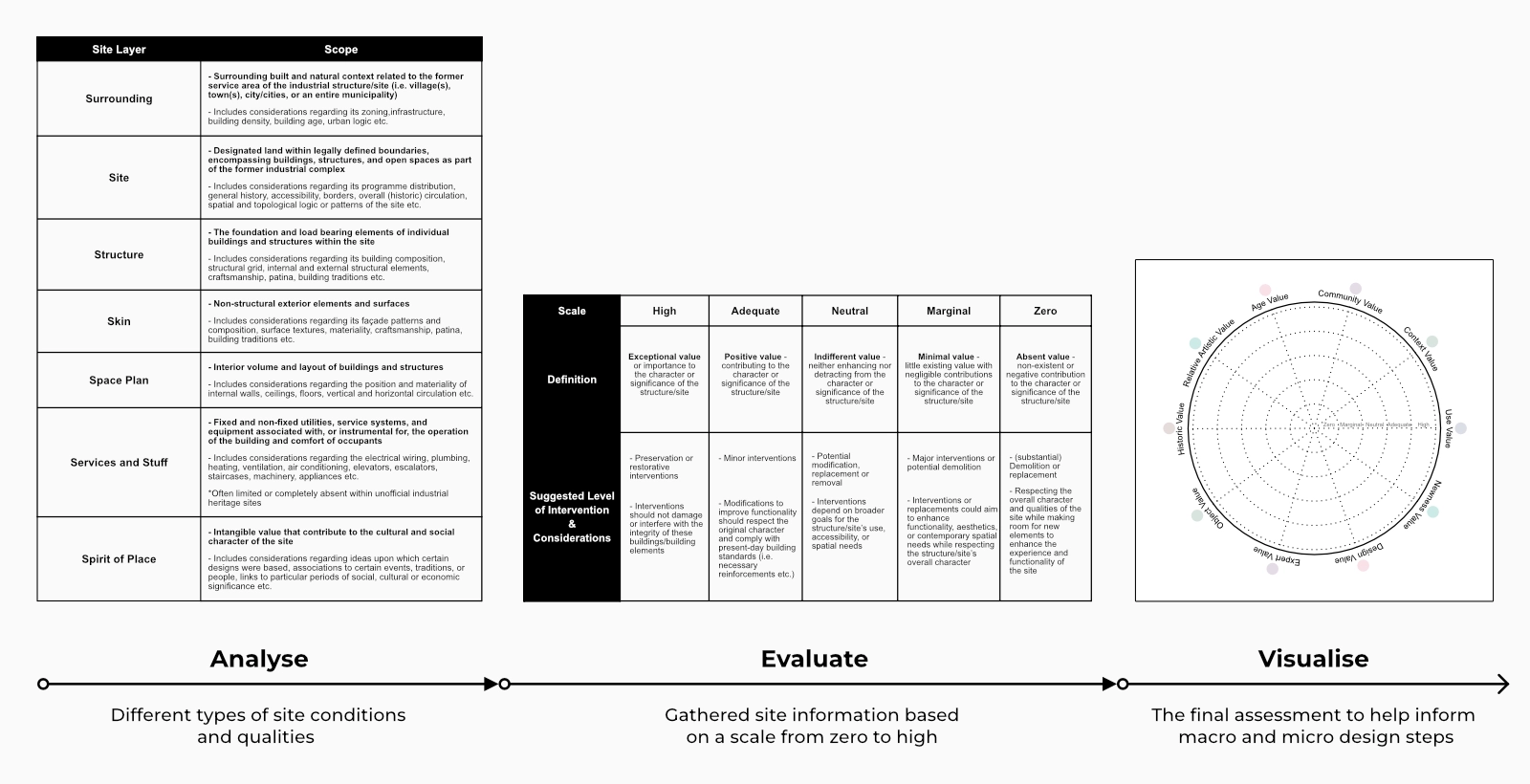

Building on existing literature and case studies, a three-step framework was developed for the adaptive reuse of ordinary industrial heritage:

Value Assessment:

Dissecting the structure(s) and site into site layers and evaluating their heritage value.

Macro Integration:

Overall strategy to integrate the site back into its broader context.

Micro Interventions:

Regeneration, adaptation, and extensions to the site, which showcase unique values and qualities of the original construction.

Value Assessment Tools

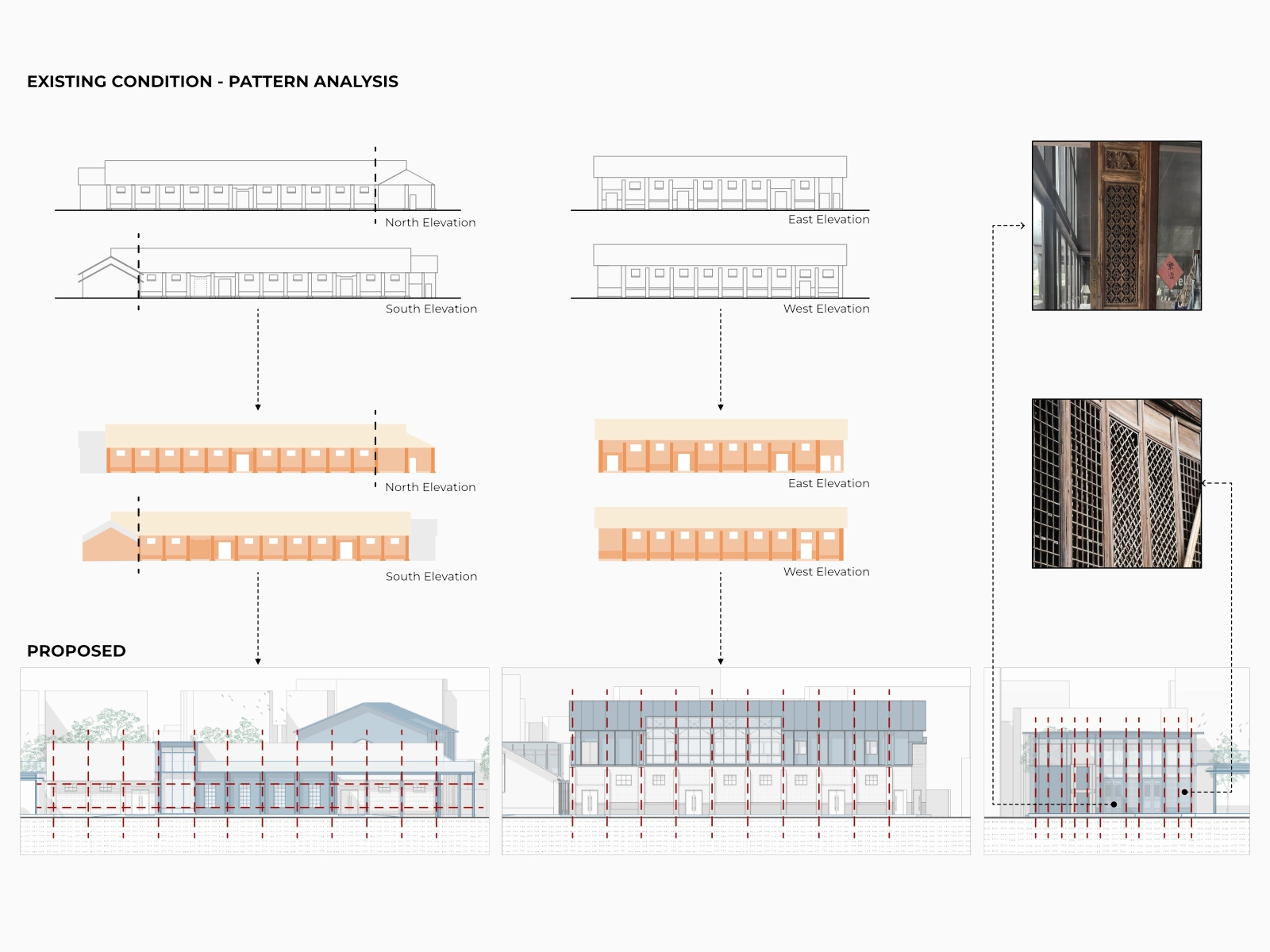

Recognising the complex character of industrial heritage, the site is dissected into seven site layers, evaluated and visualised through a ten-value radial chart.

Drawing from Brand’s spatial logic and value theories from Meurs and Riegl, this framework enables a holistic and context-sensitive understanding of place.

The Site

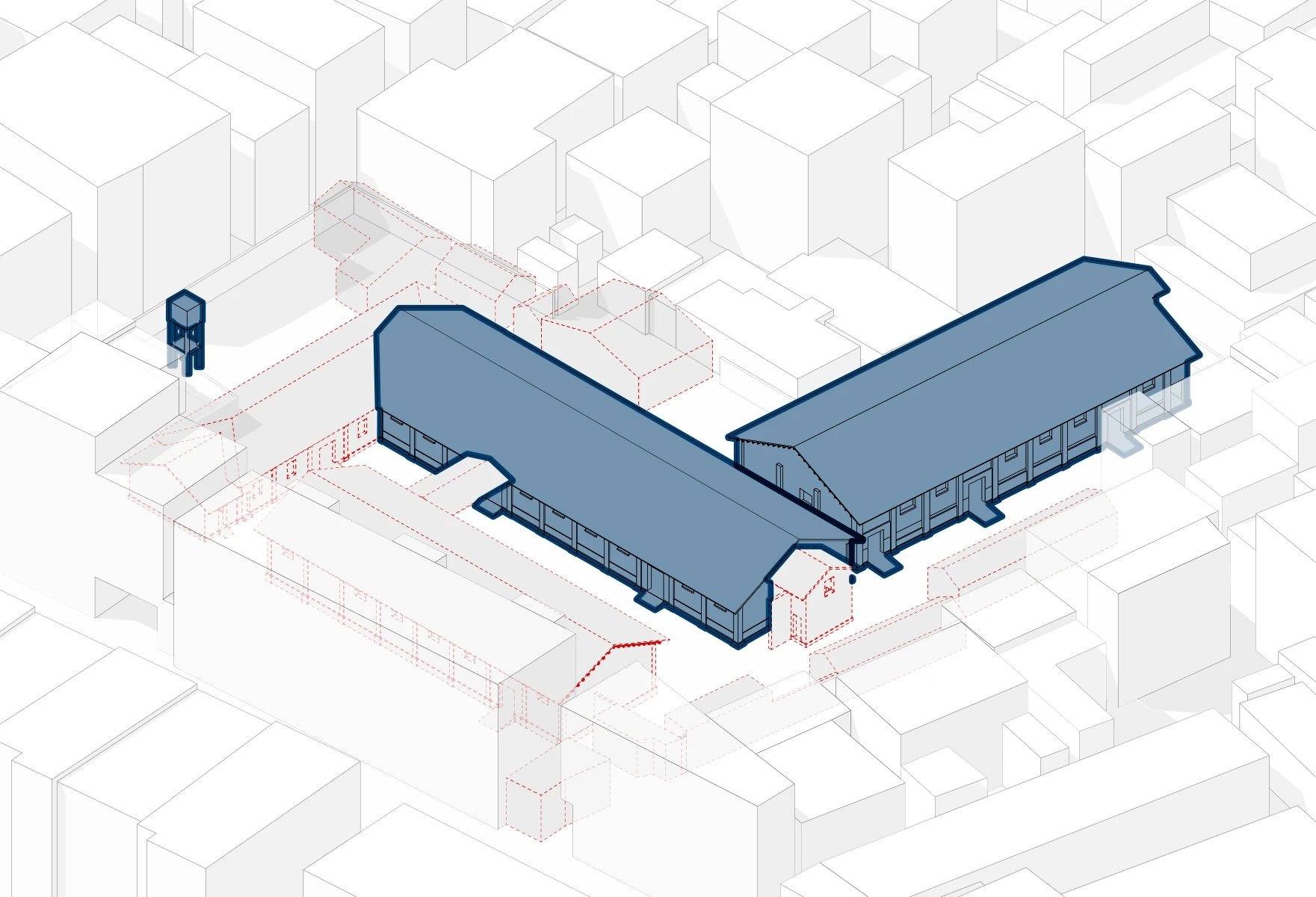

Tucked into the western centre of Qinghua Town, the Old Grain station spans nearly 4,000 m² with 4 main buildings and several ancillary structures. Built between the 1960s and 1980s, the site reflects a utilitarian and stripped-back approach, characterised by minimal detailing, straightforward spatial layouts, and fragmented outdoor areas.

Value Assessment

Alongside a broader regional analysis, the subsequent value assessment identified 5 key values:

- a distinct mezzanine space in Warehouse 2

- good structural condition in Warehouse 2 and 3

- spatial traces of the site’s utilitarian development

- he grain station’s past socioeconomic role

- repetitive and functional design language

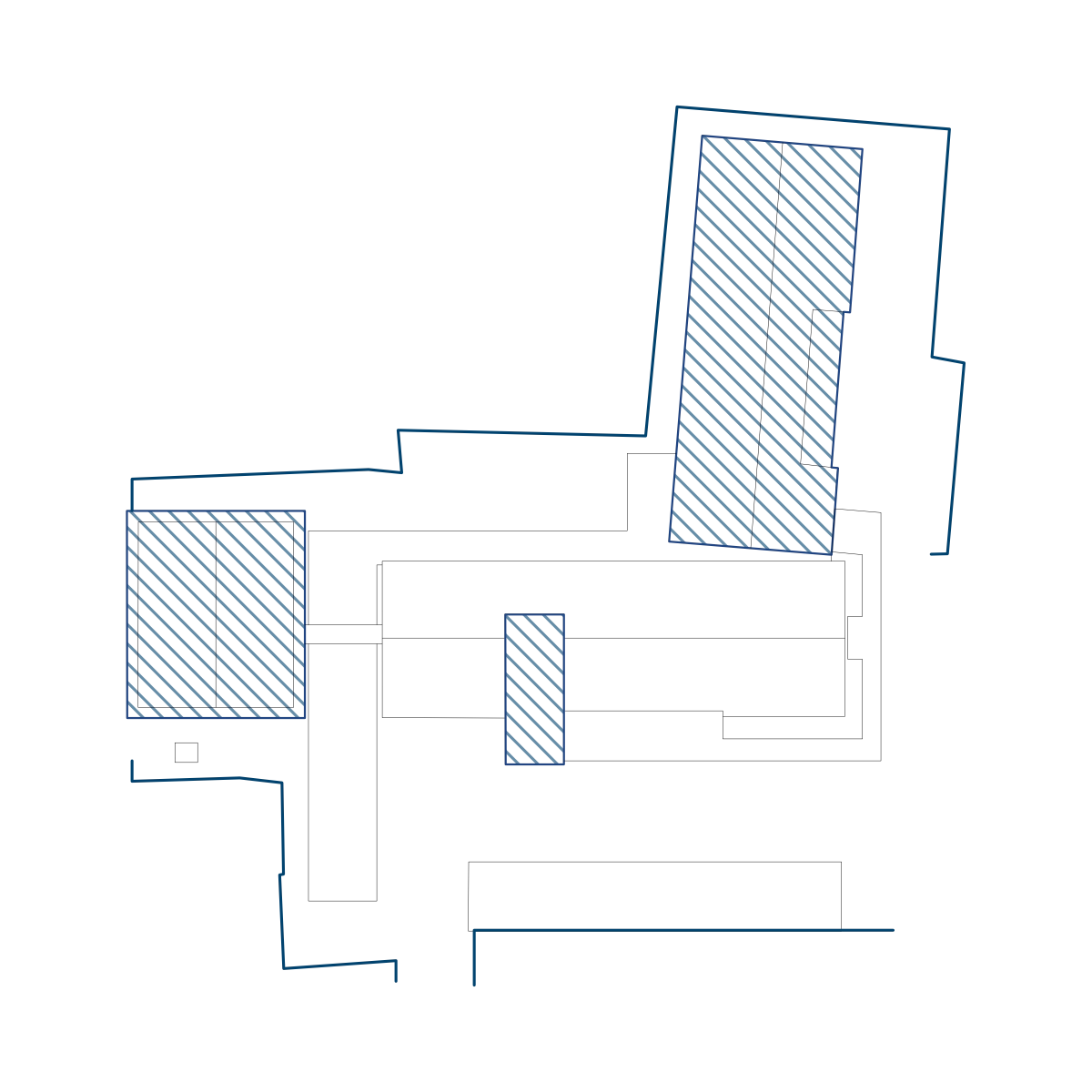

The assessment also led to the decision to retain two key buildings: Warehouse 2, for its distinctive architectural features; and Warehouse 3, for its functional layout and spatial relationship with Warehouse 2.

In contrast, Warehouse 1 and the office building are removed due to their structural limitations, low reuse potential, and spatial constraints.

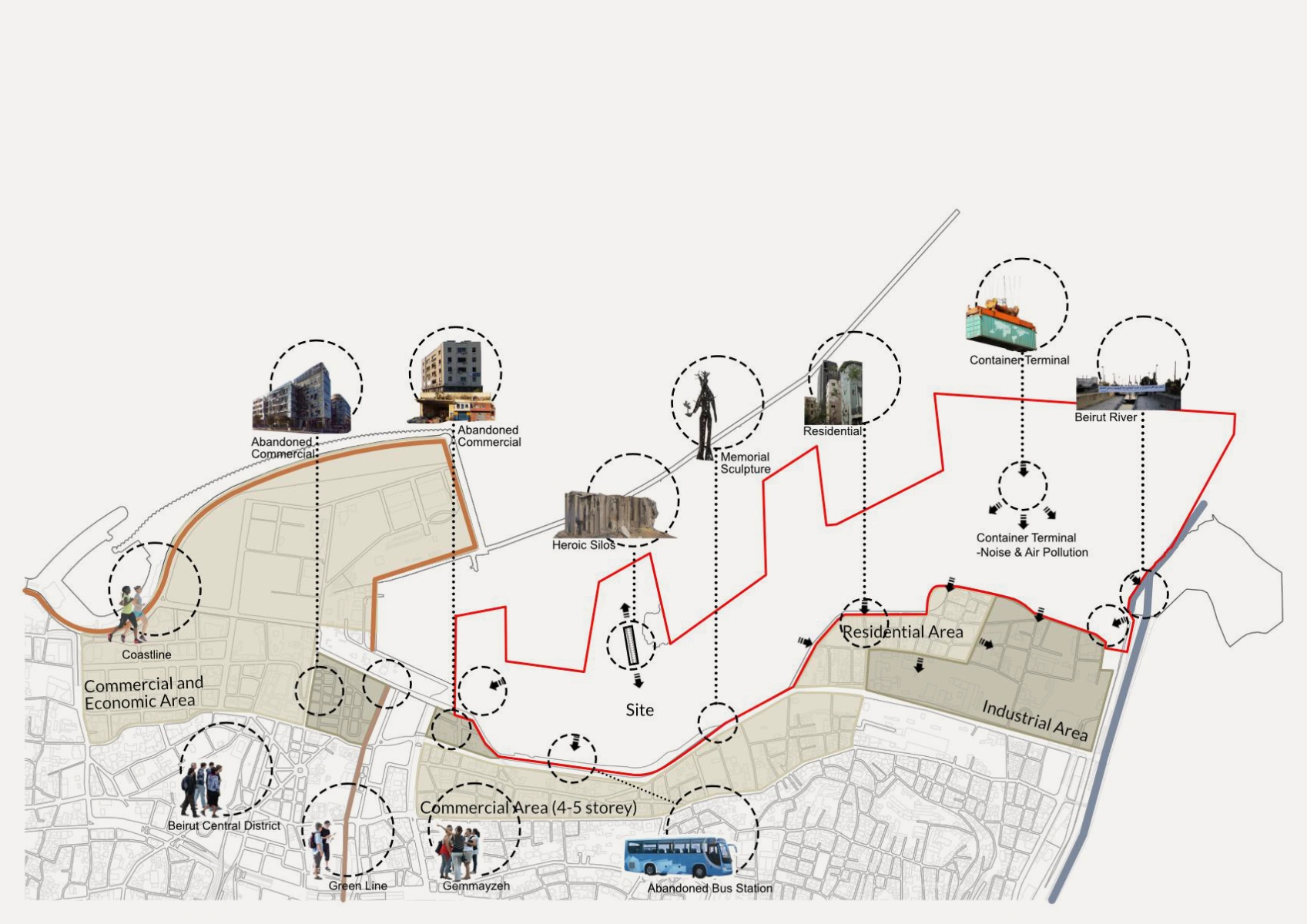

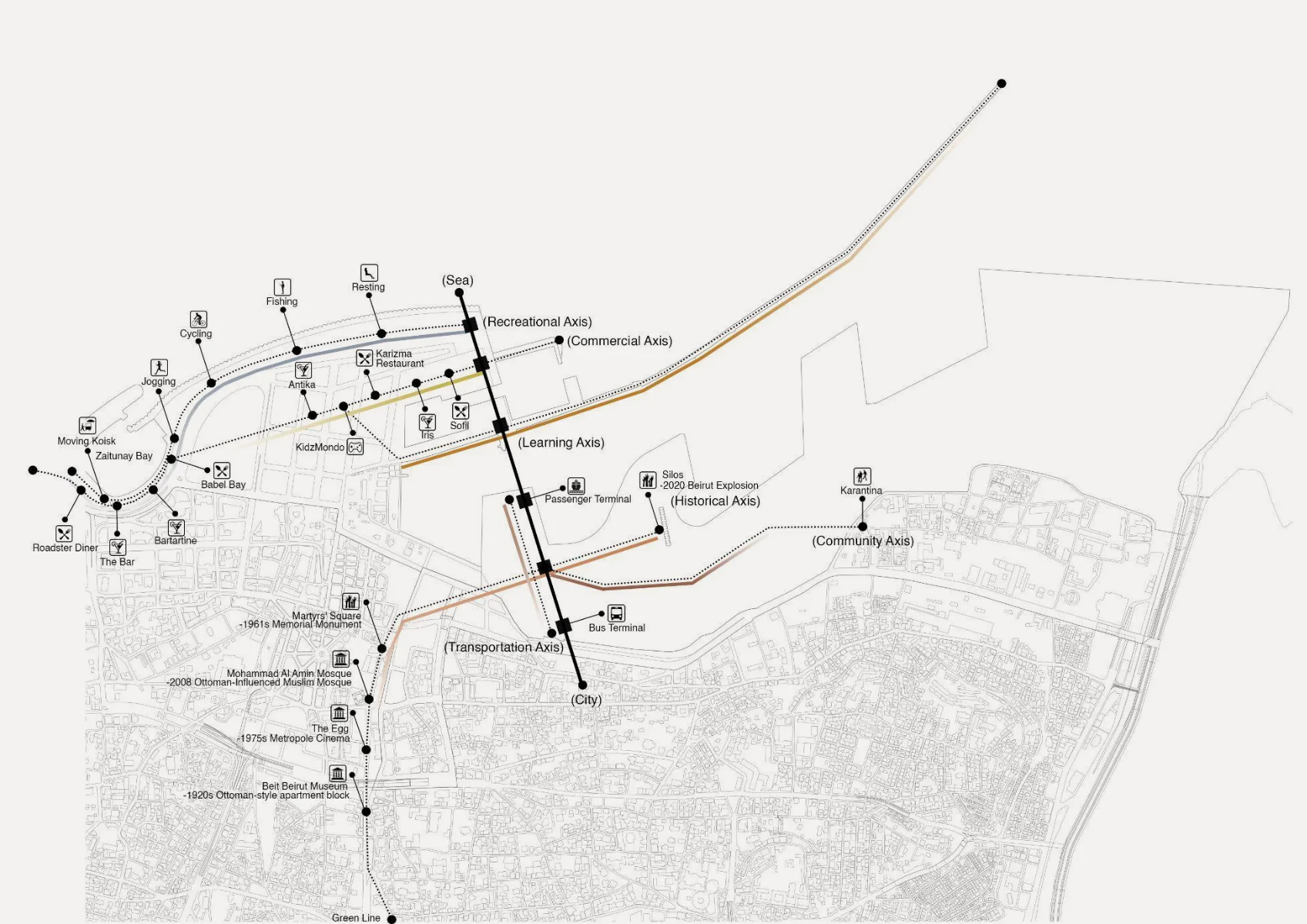

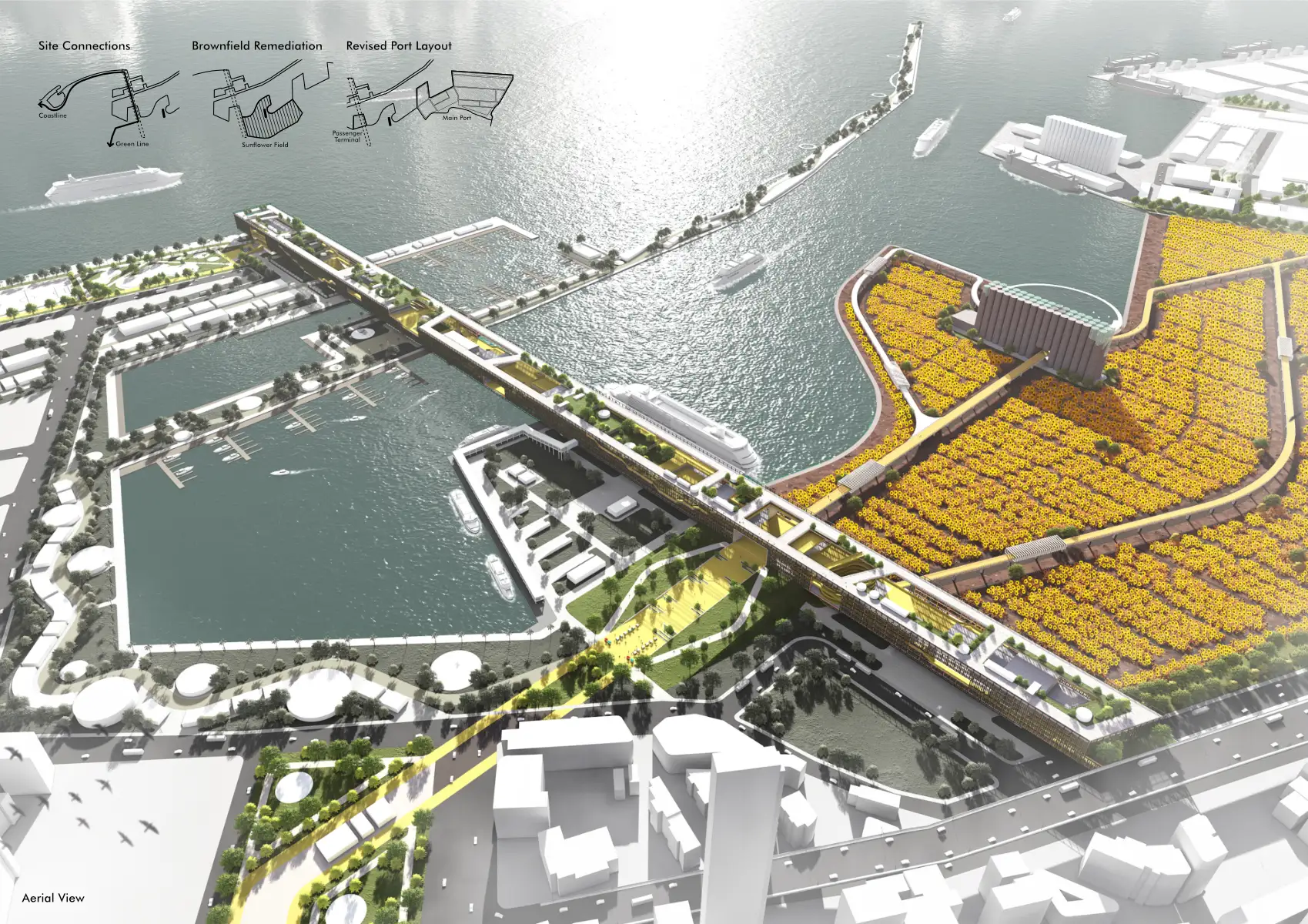

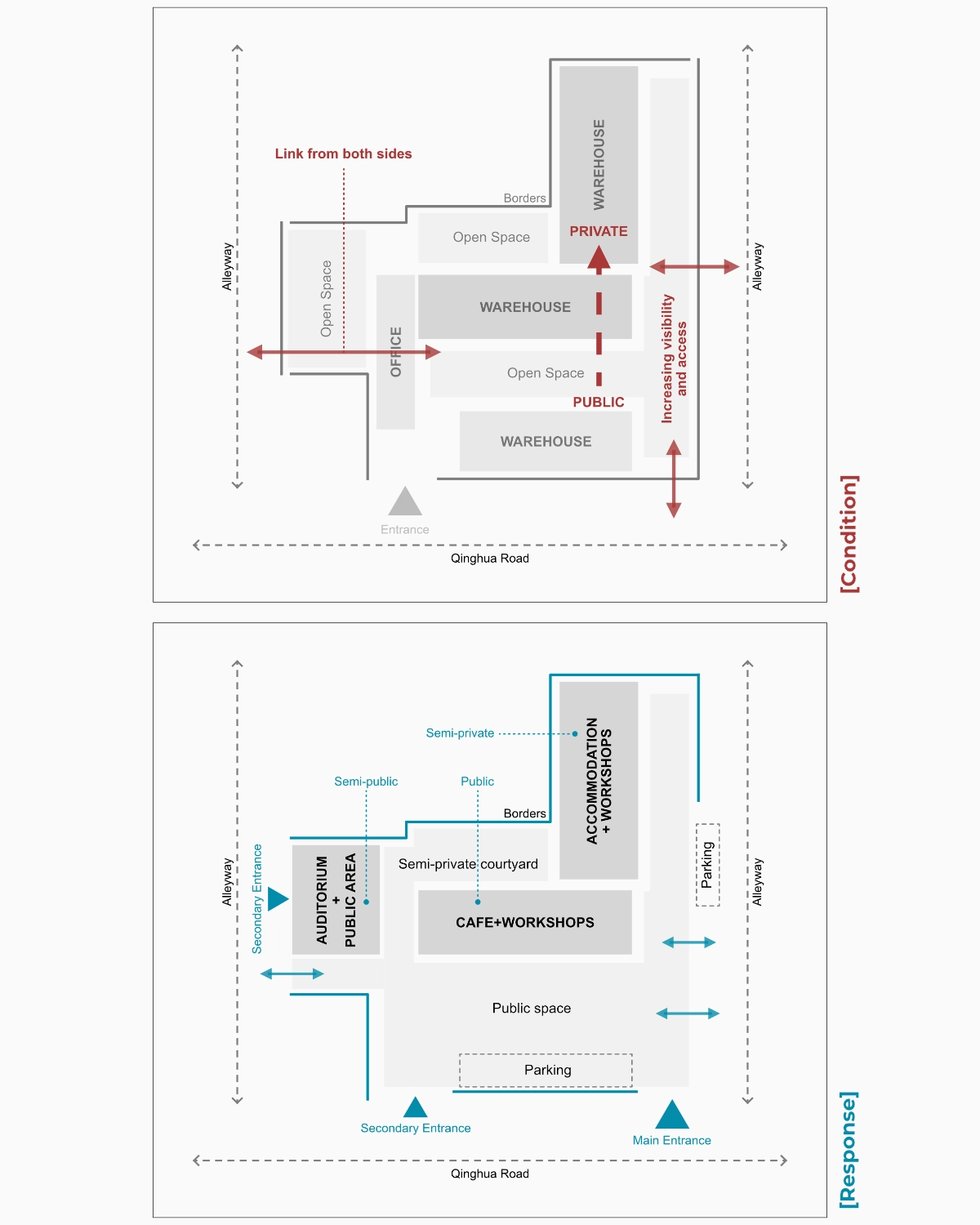

Macro Integration

Re-animate

Though formerly the county seat, Qinghua Town now faces social and economic disconnection from surrounding areas.

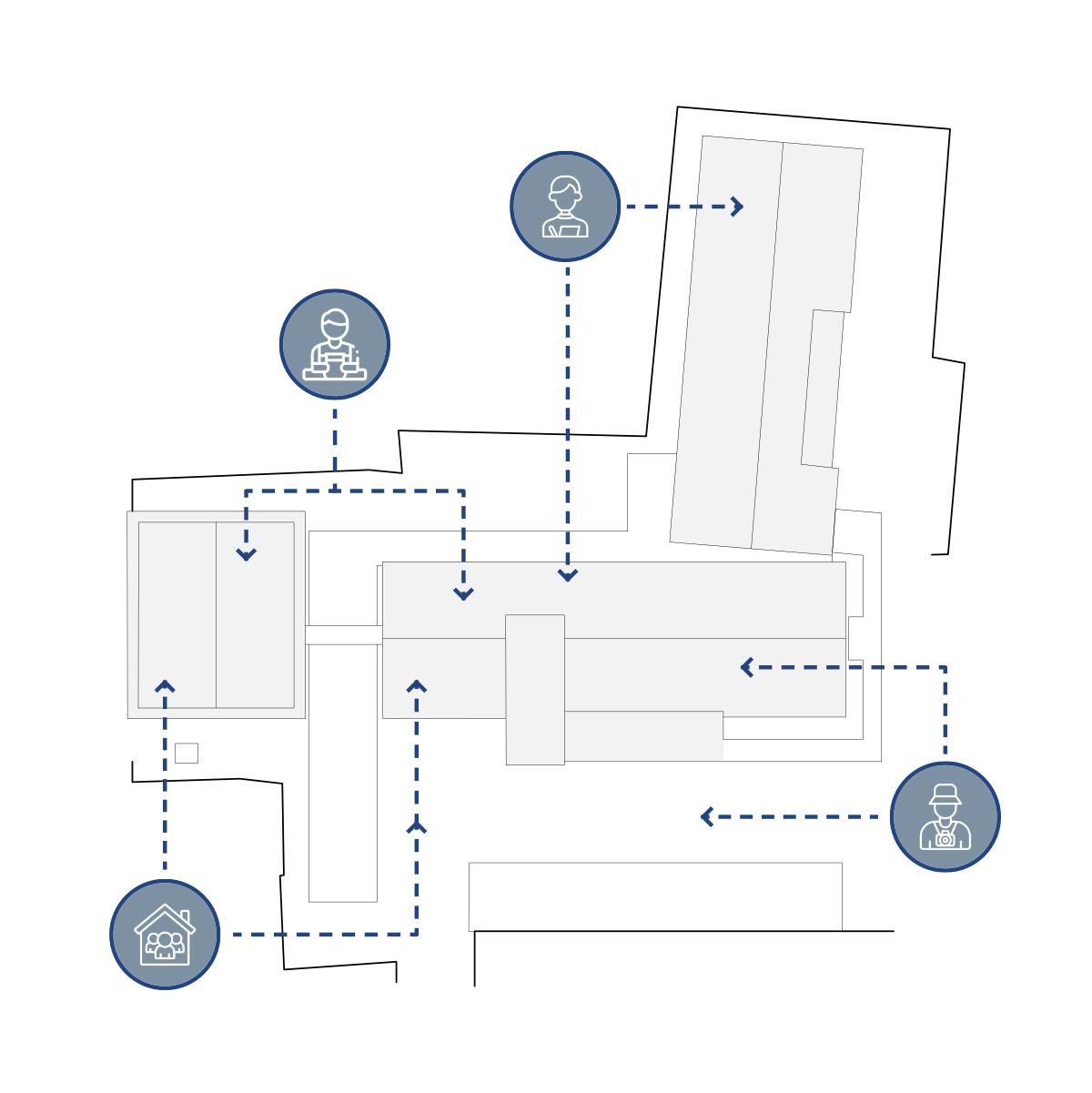

A preceding regional study identified 4 key user groups, shaping a programme centred on a research residency, a creative workshop, and a communal hall—designed to foster interaction and long-term engagement on site.

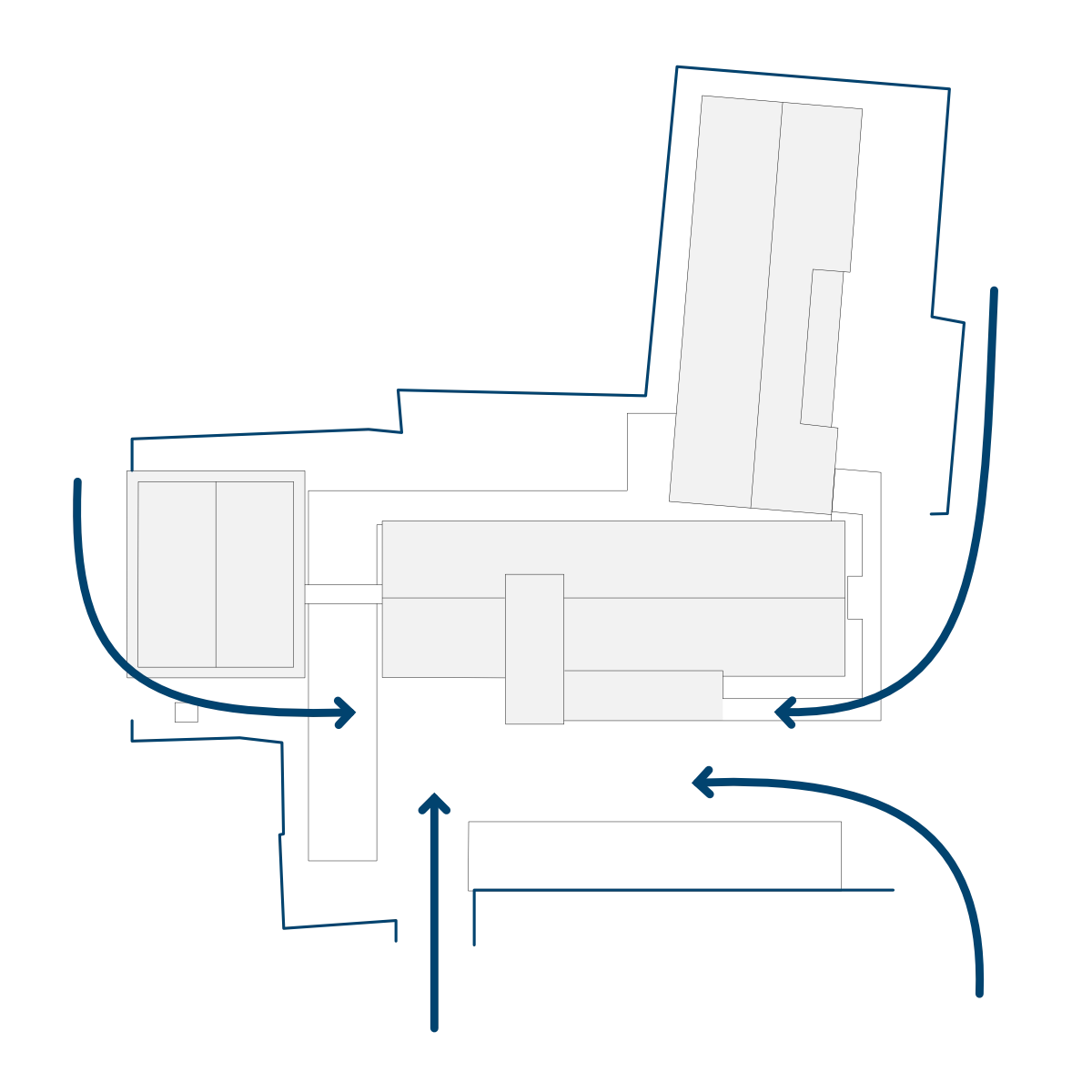

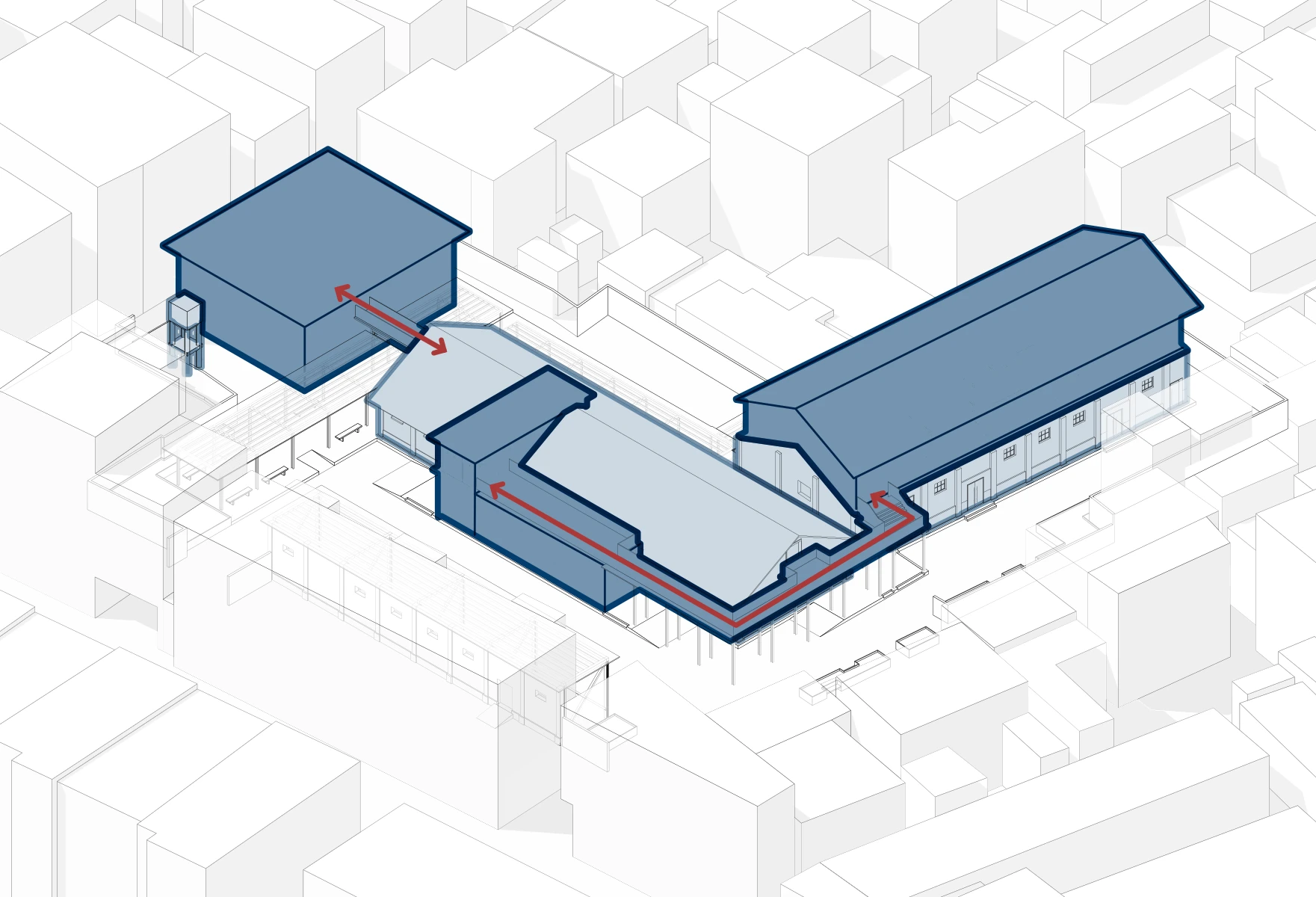

Invite

High walls and peripheral structures effectively isolated the site from its surroundings, despite its central location.

The revised layout opens key edges to adjacent streets, repositions the main entrance, and places public-facing programmes at the front, while private and larger communal spaces are set towards the rear and western edge to balance accessibility with privacy.

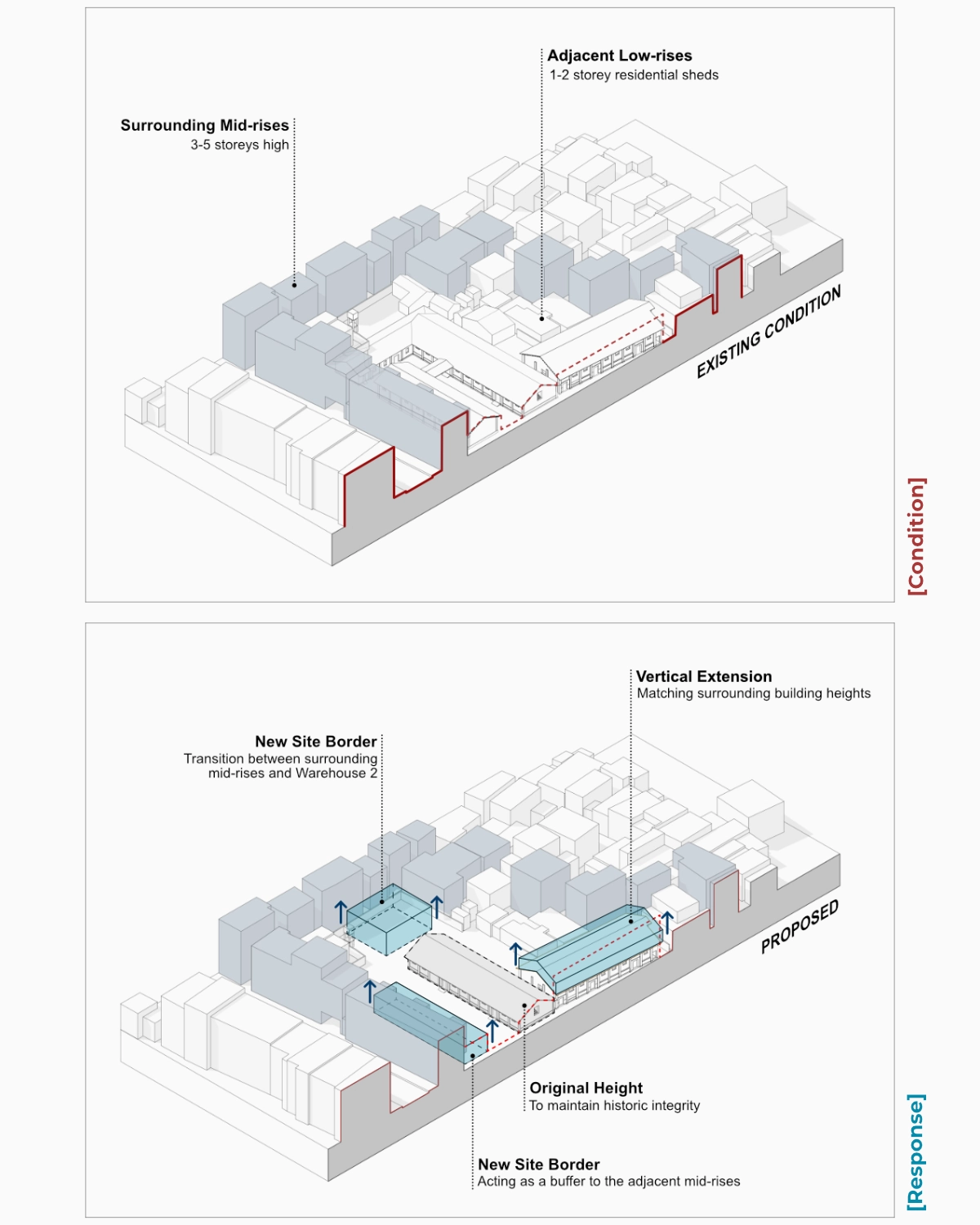

Enhance

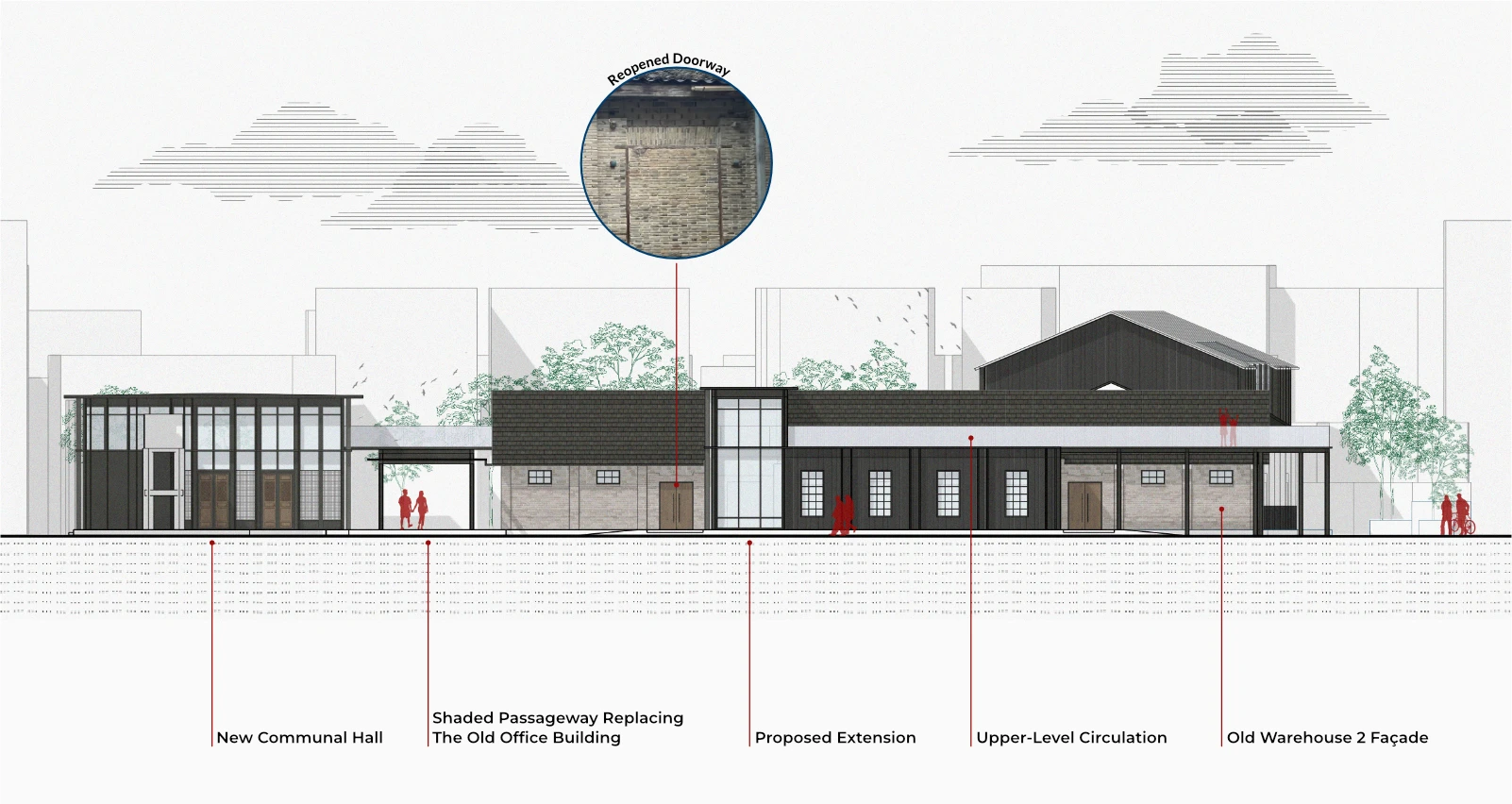

To enhance visibility and strengthen the site’s contextual presence, the massing strategy introduces a vertical extension on Warehouse 3, aligning it with adjacent buildings. A new structure on the western edge, along with targeted modifications to Warehouse 2, further supports a more seamless transition between the site and its urban context.

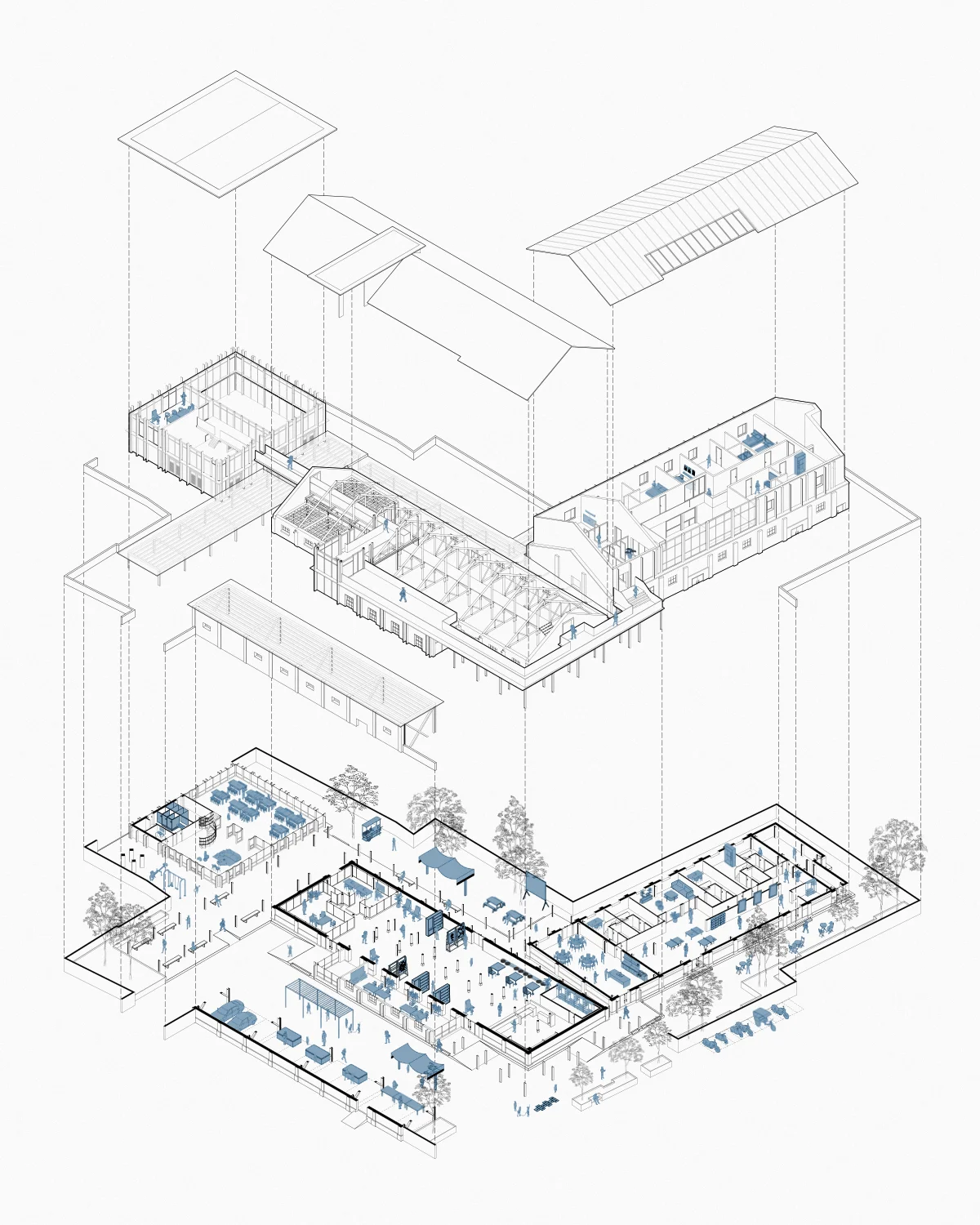

Micro Interventions

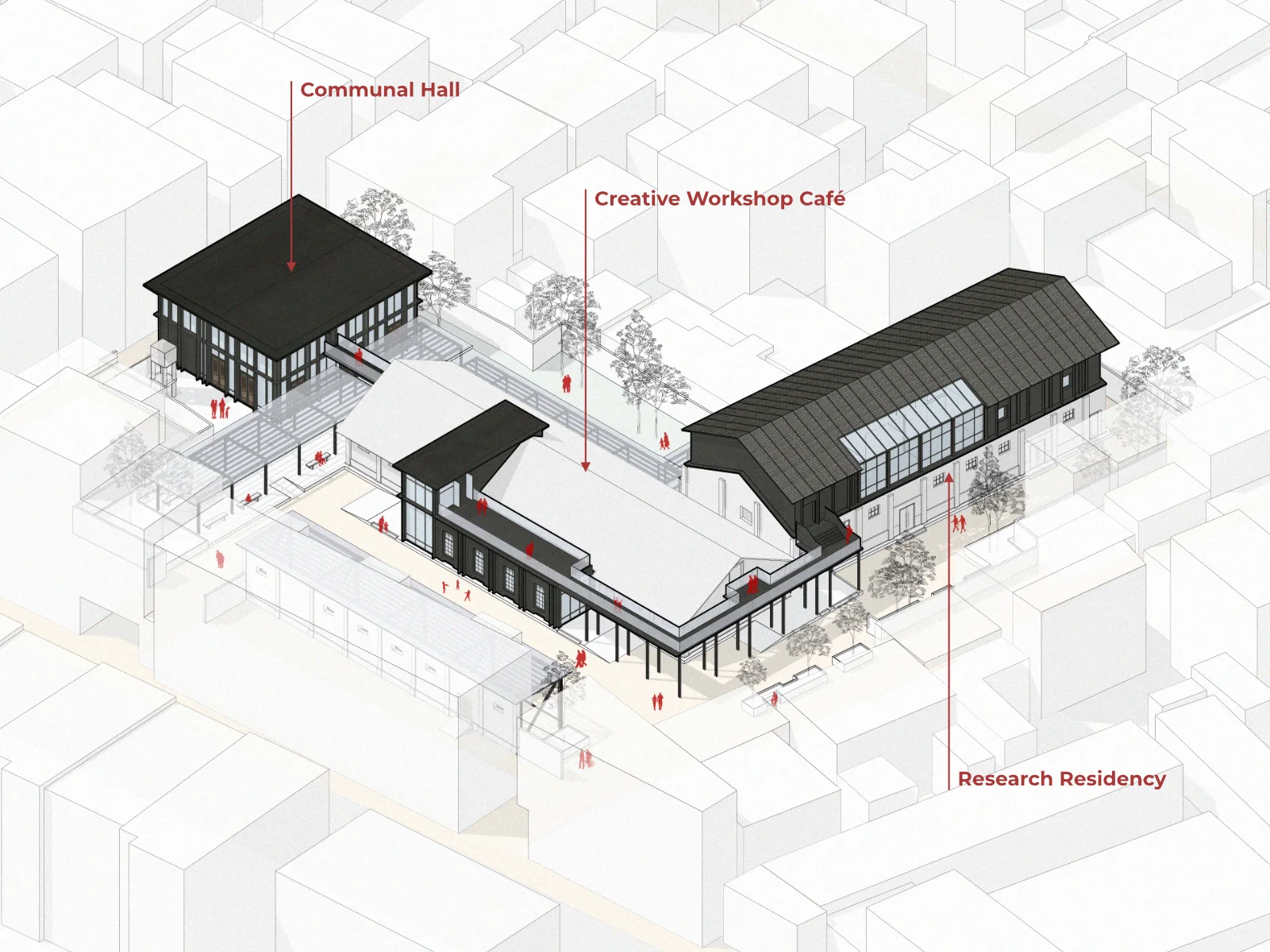

Building on the macro strategies, the micro interventions focus on accentuating, adapting and reconnecting the site through contemporary additions.

New workshop spaces are distributed across buildings, linked by an upper-level circulation route and a covered ground-level passage that replaces the former office. Additional parking provisions improve accessibility and respond to local planning gaps.

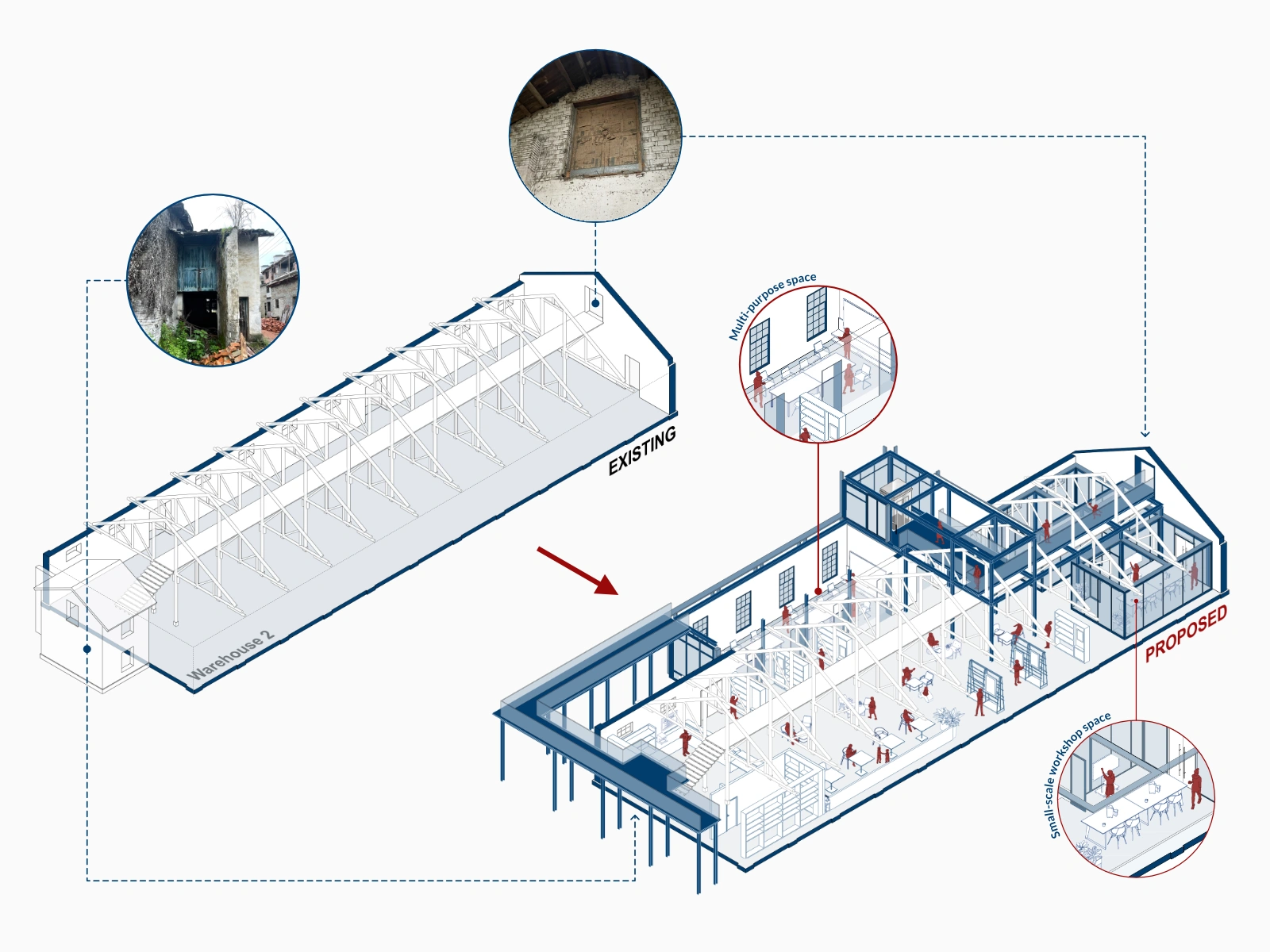

Creative Workshop Café

The conversion of Warehouse 2 into a Creative Workshop Café involves subtle yet deliberate adaptations to the existing structure. Reflecting a traditional layout, the interior is symmetrically arranged, with two enclosed rooms to the west and an open reception and café bar to the east.

The central space is intentionally left open to preserve the building’s original spatial experience. A new access point connects the mezzanine to the Communal Hall via an existing west-side doorway, while the former eastern entrance is reinterpreted as a visual threshold.

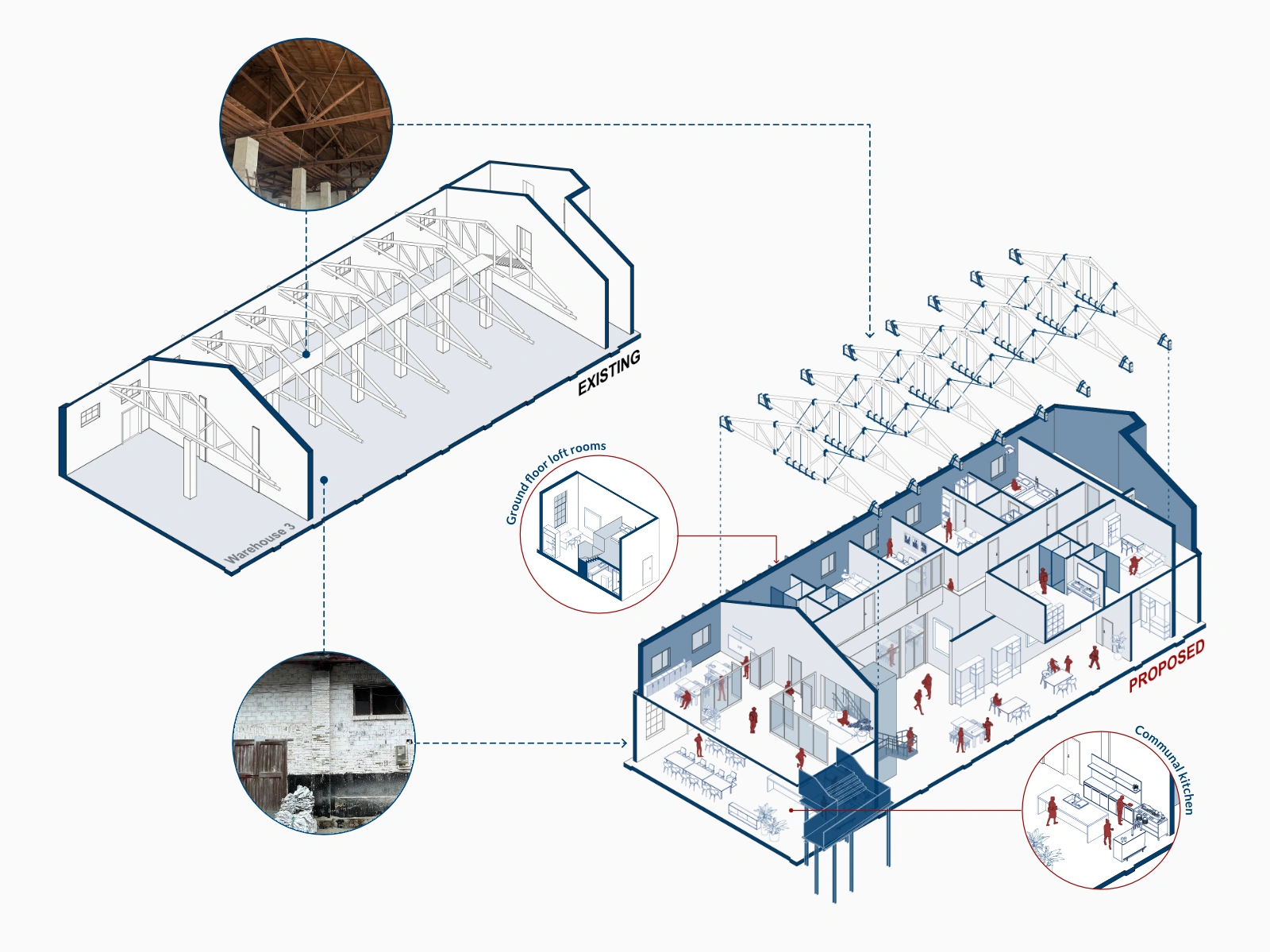

Research Residency

The Research Residency features a vertical extension to the former warehouse, providing living and working spaces for small to medium-sized research groups.

Existing masonry walls are largely retained, with a self-supporting steel frame structure inserted internally. The ground floor accommodates loft-style rooms and shared areas, while the upper level introduces larger bedrooms and multifunctional spaces. Here, the mezzanine is removed to maximise openness, with a central corridor reinstating the original axis of the building.

Communal Hall

As the only entirely new structure, the Communal Hall accommodates larger spaces not feasible within the existing buildings. Positioned along a public alleyway, it also incorporates much-needed public restrooms—accessible from both the street and within the site to serve both visitors and the wider community.

Rhythm and Materiality

Externally, the new interventions maintain the repetitive, utilitarian rhythm of the existing façades. Situated between the site and traditional Hui-style surroundings, the Communal Hall introduces subtle deviations—patterned panels, reused traditional door leaves, and vertical emphasis—to bridge traditional and industrial expressions.

Reopening the previously bricked-up doorway restores the symmetry of Warehouse 2, allowing the new extension to seamlessly continue the façade’s rhythm through vertical metal fins and enlarged windows that maximise natural light.

While aligned in material palette, the Communal Hall deliberately adopts a lighter expression to accentuate the solidity of the original constructions.

Social Character

Rooted in the site’s history, the open spaces reinforce its social and public character. With the removal of the old office building and the opening of site boundaries, previously fragmented external areas merge into a continuous public space defined by shifting thresholds—from a front plaza to a shaded passageway and an intimate rear courtyard.

Connected to the interior through existing and new access points, these spaces support flexible uses including education, culture, and recreation.